Study run by Lorna Camus, supervised by Dr Mary Stewart and Prof Thusha Rajendran.

Some background

There has been an increasing amount of studies on autistic people’s mental health, and although we do not yet have reliable population data, up to 80% of these studies’ samples have reported experiencing mental health difficulties (Lever & Geurts, 2016; Simonoff et al., 2008). This contrasts with around 20-25% of the general population, and raises the following question: why are the rates so high in autistic samples?

The recent “Not included, not engaged, not involved” report published by charities Children in Scotland, The National Autistic Society Scotland and Scottish Autism (2018) also highlighted concerns and issues in the education of autistic children in Scotland. 13% of the 1417 parents who responded indicated their children had been formally excluded from school (76% of these children were in mainstream schools). Of these children, 91% reported not getting any support to catch up on the time missed. Moreover, nearly three times as many parents (37%) reported that their children had been unlawfully excluded (an exclusion not formally recorded). Again, 91% of these children did not get support to catch up.

One of the most common other reason for missing school (aside from exclusions) was anxiety, with 63% of parents reporting their children could not attend school due to this.

Most importantly, this time out of school seems to significantly impact these children. A large number of parents reported that missing school increased their children’s anxiety and stress. Missing out on school due to anxiety and falling behind often lead to more negative feelings at and about school.

A potential source of difficulties at school is the transition to a new school. While the research on transitions to secondary school in autistic children is scarce, the research in neurotypical children has found poor transitions to have a detrimental effect on psychosocial outcomes (Riglin et al., 2013; West et al., 2010).

The impact of school on autistic children’s mental health and vice versa therefore seems to be important to understand these difficulties.

In addition to this, accessing mental health services and getting appropriate support is much harder for autistic people (Crane et al., 2018; Hallett & Crompton, 2018; Hendricks & Wehman, 2009).

These concerns over autistic people’s mental health and education correspond to the research priorities recently identified by the autistic community, which included questions about improving autistic people’s mental health and supporting their education.

This study

Considering all of the above, this study aimed to explore autistic students’ experiences of transitioning to secondary school. I wanted to know whether the secondary transition was a period of their lives which could cause new or further mental health difficulties.

13 autistic young people were recruited to be interviewed about their experience of the transition to secondary school and school more generally. 4 of them were excluded as they did not complete the main interview. The resulting 9 participants were aged 13-17 and consisted of 2 girls and 7 boys, all students in a special secondary school.

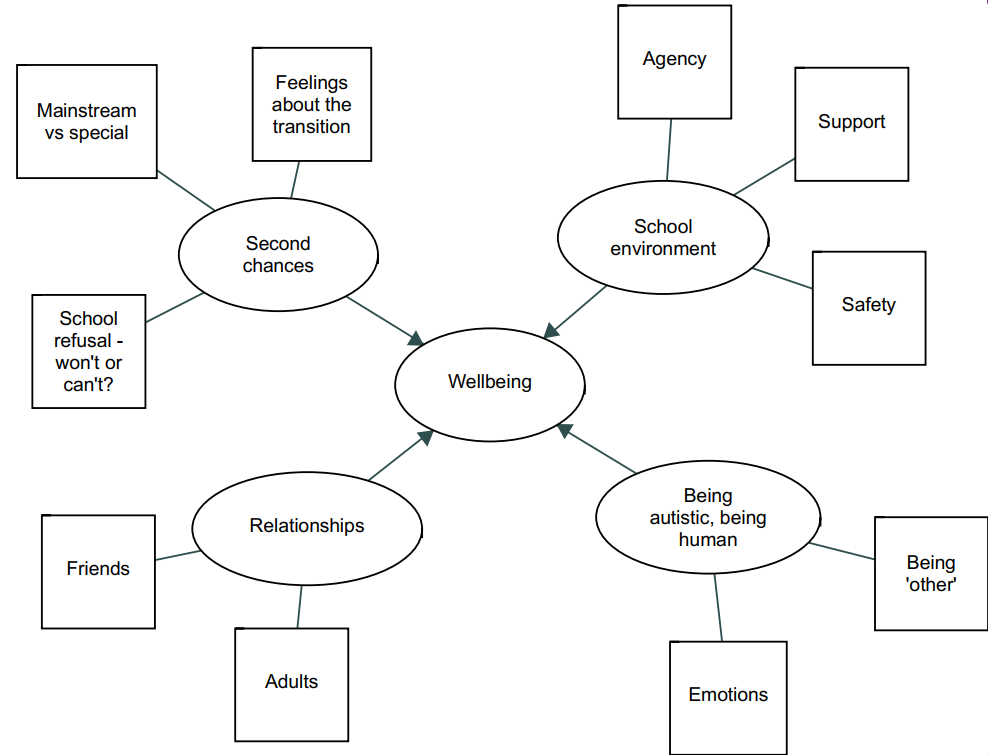

The interviews were semi-structured, face-to-face and lasted up to 45 minutes. They were analysed using thematic analysis, following steps by Braun and Clarke (2006). Semantic themes (identified at the explicit rather than underlying level of the data) were identified following a realist epistemology, in a top-down manner (following my research questions).

Themes

Note: These themes are preliminary and need further analysis (along with a 2nd rater coding). Excerpts will be provided pending ethics checks.

Implications and next steps

Implications

- For best practice in transition support for autistic students

- For inclusion as it exists presently – this calls back to recent concerns regarding the “presumption of mainstreaming” as discussed in the “Not included, not engaged, not involved report” and other works on autism and mainstreaming.

- For autism training for teachers (especially in mainstream education), to give them the tools to support students better – how can we encourage autistic-led training?

- For creating environments which foster learning but also psychological well-being in schools.

Next steps

- I hope to carry out more interviews with girls and autistic students in mainstream to make up for the lack of both in the current sample and get a more balanced view.

- I plan to further examine factors that are linked to psychological well-being and those that came up during the interviews.

- I plan to carry out a participatory study with autistic co-researchers exploring future avenues for this research projects, and to discuss topics such as intolerance of uncertainty, the double-empathy problem (Milton, 2012) and sensory experiences in autistic people.

These preliminary results are being presented at IASSIDD 2019 in Glasgow, United Kingdom and the 12th Autism-Europe Congress 2019 in Nice, France. A copy of the IASSIDD presentation can be found here. Click below for a copy of the Autism-Europe poster:

References

Bellini, S. (2004). Social Skill Deficits and Anxiety in High-Functioning Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19(2), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576040190020201

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Cheak-Zamora, N. C., Teti, M., & First, J. (2015). ‘Transitions are Scary for our Kids, and They’re Scary for us’: Family Member and Youth Perspectives on the Challenges of Transitioning to Adulthood with Autism. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 28(6), 548–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12150

Children in Scotland, The National Autistic Society, & Scottish Autism. (2018). Not included, not engaged, not involved: A report on the experiences of autistic children missing school.

Crane, L., Adams, F., Harper, G., Welch, J., & Pellicano, E. (2018). ‘Something needs to change’: Mental health experiences of young autistic adults in England. Autism, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318757048

Ghaziuddin, M., Ghaziuddin, N., & Greden, J. (2002). Depression in Persons with Autism: Implications for Research and Clinical Care. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(4), 8.

Hallett, S., & Crompton, C. J. (2018). Report on the survey carried out by the Autistic Mutual Aid Society Edinburgh, Spring 2018. 22.

Hendricks, D. R., & Wehman, P. (2009). Transition From School to Adulthood for Youth With Autism Spectrum Disorders: Review and Recommendations. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(2), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357608329827

Hughes, L. A., Banks, P., & Terras, M. M. (2013). Secondary school transition for children with special educational needs: a literature review. Support for Learning, 28(1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12012

Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315588200

Kim, J. A., Szatmari, P., Bryson, S. E., Streiner, D. L., & Wilson, F. J. (2000). The Prevalence of Anxiety and Mood Problems among Children with Autism and Asperger Syndrome. Autism, 4(2), 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361300004002002

Lever, A. G. and Geurts, H. M. (2016). Psychiatric Co-occurring Symptoms and Disorders in Young, Middle-Aged, and Older Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(6), 1916–1930.

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: the ‘double empathy problem’. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Neal, S., Rice, F., Ng-Knight, T., Riglin, L., & Frederickson, N. (2016). Exploring the longitudinal association between interventions to support the transition to secondary school and child anxiety. Journal of Adolescence, 50, 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.04.003

Riglin, L., Frederickson, N., Shelton, K. H., & Rice, F. (2013). A longitudinal study of psychological functioning and academic attainment at the transition to secondary school. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.002

Shogren, K. A., & Plotner, A. J. (2012). Transition Planning for Students With Intellectual Disability, Autism, or Other Disabilities: Data from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-50.1.16

Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., and Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric Disorders in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Associated Factors in a Population-Derived Sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 921–929.

West, P., Sweeting, H., & Young, R. (2010). Transition matters: pupils’ experiences of the primary–secondary school transition in the West of Scotland and consequences for well-being and attainment. Research Papers in Education, 25(1), 21–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520802308677